We’ve all been there. You’re deep in the flow of building a new feature when that dreaded notification arrives: “Critical bug blocking release.” Most of us instinctively groan, but over the years, you can learn to recognize these moments as hidden opportunities.

"…a good part of the remainder of my life was going to be spent in finding errors in my own programs."1

The best software engineers don’t run from bugs, they actively hunt them down. When you first notice this pattern during your early career, it might seem counterintuitive. Why would top performers chase problems instead of showcasing their skills through fresh features? The answer can transform your approach to engineering.

Why You Should Love Bugs

“If debugging is the process of removing software bugs, then programming must be the process of putting them in.”2

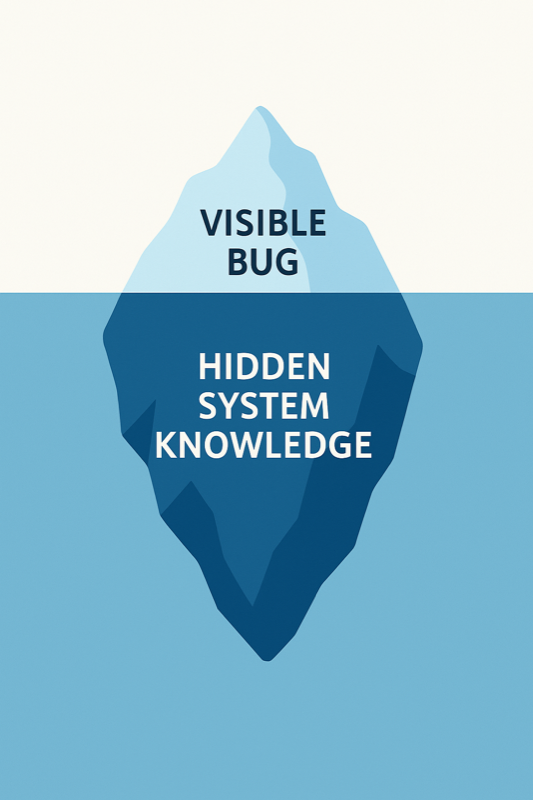

Debugging forces you to develop an intimate understanding of how systems truly work together. A single day spent tracing an elusive bug often teaches more about your codebase than a week of implementing new functionality. You’re compelled to follow data as it flows across boundaries, uncovering the actual architecture rather than the one in the documentation.

There’s also something uniquely satisfying about fixing bugs that feature work rarely provides. Users immediately feel the impact when pain points disappear. While many new features ultimately fail A/B tests or see limited adoption, bug fixes create permanent improvements. They’re the clearest way to demonstrate your direct impact on user experience.

Joel Spolsky, co-founder of Stack Overflow, explains this brilliantly in his classic essay “Things You Should Never Do”. He warns that a full rewrite throws away years of hard-won knowledge (including countless subtle bug fixes) and sets teams back to zero.

As you advance in your career, you’ll notice that senior and staff engineers approach bugs differently than juniors. While newer engineers chase “cool” feature work, veterans recognize that owning and resolving complex bugs can accelerate career growth by demonstrating rare, high-impact skills that cross team boundaries.

Debugging As a Premium Skill

“Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it.”3

It’s good to refine an approach that turns chaos into clarity through repeated debugging sessions. You can start by being proactive rather than reactive. Regularly scanning dashboards, crash logs, and user feedback helps spot issues before they escalate to critical status. When prioritizing, it’s best to consider both severity and frequency—a minor bug affecting thousands demands attention before a major one affecting just a handful of users.

Debugging isn’t just one skill—it involves sharp questioning, deductive reasoning, clear communication, systems thinking, and holistic understanding. As AI-generated “vibe coding” becomes more common, engineers who can deeply understand and fix code will become even more valuable. This requires patience and technical mastery far beyond just prompting an AI.

Reproduction is where the real detective work begins. You should systematically change one variable at a time until you can trigger the bug on command. This requires testing different versions, languages, devices, network conditions, experiments, and user paths—not just trying once and giving up. Bugs might appear intermittent or path-dependent, so multiple attempts and thoughtful investigation are essential.

The most common mistake even experienced engineers make is settling for surface-level fixes. Adding random null checks might make the error disappear temporarily, but without understanding the root cause, you’re just waiting for it to resurface in a different form. These “blind fixes” lead to fragile software that becomes increasingly difficult to maintain.

From Finding to Fixing Systematically

“Fix the cause, not the symptom.”4

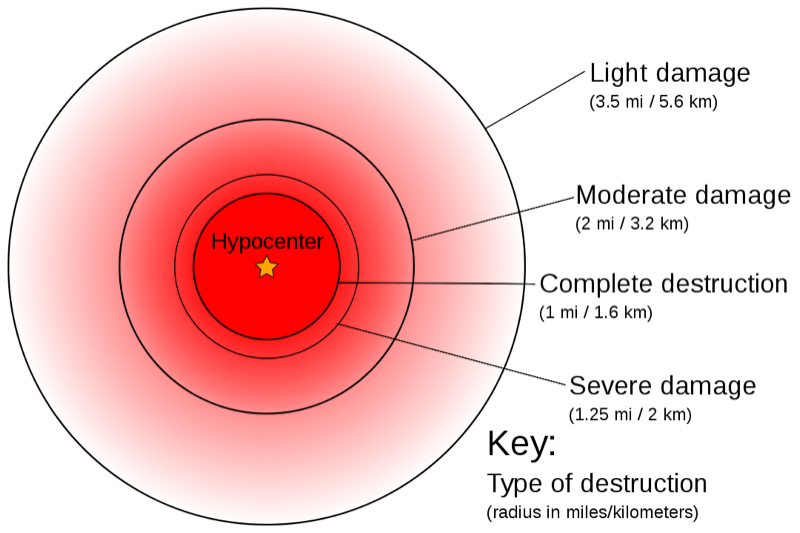

Before fixing anything, it’s crucial to assess and document the “blast radius” by asking when the issue started, who and where it impacts, and what product versions are affected. This helps you communicate frequent updates to leadership and stakeholders—even if there’s no fix yet—maintaining trust and reducing panic.

You shouldn’t wait for clarity to write—writing your thoughts down is what creates clarity and uncovers next steps. Always document reproduction steps, failed attempts, blast radius info, and hypotheses while debugging. Even half-baked notes are powerful because they build momentum, reduce confusion, and help communicate progress to others effectively.

Mapping the system visually can save countless hours. Drawing out how data flows often reveals bottlenecks before you’ve even opened your IDE. When working with others, you’ll find that regular structured updates build trust. A simple format of “current understanding of blast radius / working hypothesis / next investigative step” keeps everyone aligned while giving you space to work.

Before implementing a fix, you should deeply understand the end-to-end flow, the intended behavior, and where reality deviates. Breaking down the system into smaller steps, narrowing down the problem area through a process of elimination, and asking better questions based on where things fail are all valuable techniques. Strong debuggers act like detectives: they map out the flow precisely, isolate the problem, and only fix after gaining clarity on why things broke.

Advanced Techniques That Pay Dividends

“The most effective debugging tool is still careful thought, coupled with judiciously placed print statements.”5

Over time, you can incorporate more advanced techniques that dramatically improve debugging efficiency. Proper observability through strategic logging, traces, and metrics can slash resolution times. For every bug you encounter, it’s good to write a failing test first, ensuring it never returns. Static analysis tools with strict rules can catch entire categories of issues before they reach production.

“Testing shows the presence, not the absence, of bugs.”6

This sober reminder from Dijkstra helps us maintain the right mindset: even when all tests pass, we can only say “no bugs were found,” never “no bugs exist.” It’s why comprehensive test suites are so valuable, yet we must remain vigilant for edge cases they miss.

You might even embrace concepts from chaos engineering, deliberately injecting small failures in controlled environments to build resilience. And after each significant incident, it’s beneficial to focus on blameless learning: what systemic improvements would prevent similar issues, rather than who made a mistake.

Attending CIR (Critical Incident) reviews, learning from outages, and applying those lessons is a major career hack for fast growth. By understanding the broader categories of software failures (functional, usability, integration, concurrency, security, performance, user error), you can better diagnose the true underlying problems and build more robust systems.

Why This Matters Even More in the Age of AI 🤖

“Beware of bugs in the above code; I have only proved it correct, not tried it.”7

As LLMs churn out boilerplate at light-speed, humans who can diagnose the unpredictable edge cases become priceless. Debugging isn’t just future-proof, it’s future-pivotal.

In a world where anyone can generate code through prompts “vibe coding”, the engineers who understand why systems break and how to fix them properly will be the ones who create lasting value. While AI can suggest fixes for obvious issues, it can’t yet integrate the deep contextual understanding that comes from years of debugging diverse systems.

A Field-Tested Debugging Playbook That Actually Works (16 Steps)

For those interested in specific techniques, here’s a comprehensive debugging framework refined by elite engineers over years. This covers the complete debugging lifecycle from detection to verification:

Proactive Bug-Hunting – Dashboards, crash logs, user reviews—don’t wait for Jira tickets. Great engineers actively hunt for bugs rather than waiting for assignments.

Severity × Frequency First – Tiny bug hitting thousands > critical bug hitting three. Use this framework to quickly assess whether a bug is urgent, trivial, or somewhere in between.

Methodical Reproduction – Change one variable at a time until the bug obeys you. Understand when and why the bug occurs, forming the foundation for prioritizing and fixing it effectively.

Live Note-Taking – Half-baked notes > perfect memory; they morph into incident reports and promo blurbs. Writing improves retention, narrows the search area, and helps you communicate progress.

Visual System Mapping – If you can draw it, you can usually fix it. Understand which components are involved, how they communicate, and what data formats they expect.

Root-Cause or Bust – Guardrails over band-aids; fix classes, not symptoms. Avoid “blind fixes” that paper over symptoms without addressing underlying issues.

Observability Everywhere – Logs + traces + metrics (OpenTelemetry!) slash MTTR. Proper observability is the foundation of efficient debugging.

Test-First Fixes – Write the failing test, then squash the bug—make sure it never resurfaces. This ensures regressions are caught immediately.

Static Analysis on “Fail” – Turn compiler or linter warnings into errors; wipe out whole bug families. This prevents entire categories of bugs from ever reaching production.

Chaos Engineering – Inject small failures in staging so prod outages feel like rehearsed drills. This builds resilience and prepares teams for when things inevitably go wrong.

Blameless Post-Mortems – Trigger → Impact → Detection → Fix → Actions. Improve systems, not people-blame. Focus on systemic improvements that would prevent similar issues.

Real-World Example: Critical Incident Reviews

At a production computer vision company, we implemented a simple but powerful CIR (Critical Incident Review) process. As our models were deployed to more customers, they inevitably encountered new data patterns and edge cases in production, causing performance degradation that became harder to track and debug.

The problem was visibility—bugs and failures in live systems weren’t reaching the wider engineering team, making it difficult to build shared context, spot patterns, and respond quickly.

Our solution was structured CIR reviews that documented five key questions:

- What happened?

- How did we detect it?

- What was the root cause?

- How did we fix it?

- How can we prevent it?

The engineer who led the fix would then run a short CIR deep dive to bring others up to speed. This approach distributed expertise, encouraged collective debugging, and surfaced better ideas—you never know who on your team holds a key insight that could unlock a difficult problem.

Version-Control Forensics – Use

git bisect,blame, and diff-driven bisection to binary-search your commit history and pinpoint exactly which change introduced the regression. This is a daily lifesaver for bugs that “used to work yesterday,” especially as AI assistants generate more code diffs.Record & Replay Debugging – rr (native code) and WinDbg/Visual Studio Time Travel Debugging let you step both forward and backward through execution. Chrome DevTools’ Recorder replays user flows but does not yet support reverse single-stepping. This eliminates “can’t reproduce on my machine” problems by allowing you to replay the exact failing run—critical for Heisenbugs and concurrency issues.

Feature Flags & Canary Releases – Decouple deploy from release by rolling fixes out to 1% of traffic first, watching dashboards, then dialing up—or hitting the kill-switch in seconds if metrics spike. Essential for hot fixes to revenue paths or when the root cause is still murky.

Runtime Binary Search Debugging – For complex systems where the bug is hidden in a large execution path, divide and conquer at runtime. Insert checkpoints, logs, or assertions at strategic middle points in the execution flow to determine which half contains the failure, then recursively narrow down the issue. Unlike git bisect which works on commit history, this operates directly on code execution paths.

Environmental Context – Track what works in one environment but not another. Often bugs exist only in production due to scale, data variations, or configuration differences that testing environments don’t mirror.

The beauty of this approach is that it scales with experience. Junior engineers can start with methodical reproduction and note-taking, while seniors can incorporate more advanced techniques like observability and chaos engineering. Together, these 16 techniques cover the full debugging lifecycle: detect → localize → inspect → fix → ship → verify.

When Debugging Makes You Want to Quit

I know firsthand that debugging can be painfully hard. We’ve all been there—staring at the screen at 2 AM, eyes burning, wondering if we chose the wrong career. The endless cycles of “I think I fixed it” followed by new errors can make even the most dedicated engineers want to give up.

But in those dark moments, I’ve found comfort in the words of the computing pioneers who came before us. These titans of our industry faced the same struggles, often with far fewer tools and resources than we have today. Their hard-earned wisdom has pulled me back from the brink more times than I can count.

Here are the quotes I return to when debugging seems impossible—timeless insights from the OGs of software engineering that help me keep going:

"…a good part of the remainder of my life was going to be spent in finding errors in my own programs."1

This was the moment when one of computing’s earliest pioneers realized what we now all know: debugging isn’t just part of the job—it often is the job. If Maurice Wilkes could make peace with this in 1949, using paper printouts and physical switches, we can certainly embrace it with our modern tools.

“Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it.”3

Kernighan’s law reminds me that my struggles aren’t from lack of skill but from the inherent complexity of the task. When I feel inadequate during a difficult debugging session, I remember that this feeling is by design—and I should focus on writing clearer code in the first place.

“If debugging is the process of removing software bugs, then programming must be the process of putting them in.”2

This always makes me smile, no matter how frustrated I am. It reframes the entire problem: bugs aren’t unexpected failures in our perfect systems; they’re the natural byproducts of our imperfect, human creation process.

“The most effective debugging tool is still careful thought, coupled with judiciously placed print statements.”5

When I find myself reaching for increasingly complex debugging tools, this quote grounds me. Sometimes the simplest approaches—thinking methodically and adding strategic log statements—are still the most powerful.

“Fix the cause, not the symptom.”4

The core of root-cause analysis in one sentence. This mantra has saved me countless hours of recurring bugs and repeated fixes.

“Testing shows the presence, not the absence, of bugs.”6

A humbling reminder that even our most thorough testing can only prove that bugs exist, never that they don’t. It’s why we must remain vigilant and humble, even when all tests pass.

“Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.” (Linus’s Law)8

When I’m stuck, this reminds me to bring in another pair of eyes. The bug that’s been tormenting me for days might be obvious to someone with a different perspective.

“Beware of bugs in the above code; I have only proved it correct, not tried it.”7

Even the legendary Donald Knuth—perhaps the greatest computer scientist of all time—acknowledged the gap between theoretical correctness and practical execution. If Knuth remained humble about his code, we should all approach debugging with the same humility.

When the debugging process feels overwhelming, I return to these quotes like old friends. They remind me that my struggles aren’t unique—they’re part of a shared experience that connects me to the greatest minds in computing history. The bugs I face today are just the latest chapter in a story that began with the first computers.

Technical Terms Glossary

- A/B Testing: Comparing two versions of a feature to determine which performs better

- Binary Search: A divide-and-conquer algorithm that efficiently narrows down a search space

- Blast Radius: The scope and impact of a bug or outage across systems and users

- Chaos Engineering: The practice of deliberately introducing controlled failures to build resilient systems

- IDE: Integrated Development Environment, a software application for writing code

- LLM: Large Language Model, an AI system trained to understand and generate human language

- MTTR: Mean Time To Recovery/Resolution, a metric measuring how quickly systems recover from failures

- OpenTelemetry: An open-source framework for collecting and exporting telemetry data

- Post-Mortem: A process to analyze what happened after an incident to prevent similar issues

- Rubber Duck Debugging: The practice of explaining code line-by-line to an inanimate object (like a rubber duck) to find bugs through the process of detailed articulation

- CIR: Critical Incident Review, a process to analyze what happened after an incident to prevent similar issues

- Static Analysis: Examining code without executing it to find potential problems

- Vibe Coding: Writing code by copying patterns without deep understanding of the underlying systems or principles; often accelerated by AI tools